Metaphysics

19/09/2015

The Time Is Now

Time, the sensation of tense one seems to find oneself surrounded by. My birthday was last month, my mother’s birthday is next month, neither her birthday nor my birthday are happening now. You were late for class this morning, to be specific you were five and a half minutes late, unlike me, I was five and two thirds minutes early; whereas Fred arrived exactly on time. ‘Fred arrived exactly on time’: is this to say Fred perhaps mounted time and rode it here? Or is this to say that Fred’s penetration of the threshold, and time’s penetration of the threshold occurred simultaneously? Yet if either of these were the case, that would mean that time was not in the room before Fred arrived, which is illogical to presume. In the particular case of Fred it would likely be more proper to state that Fred crossed the threshold at the precise moment which Fred had previously agreed to cross the threshold upon. What then is this moment I speak of? It seems to be some very general measurement of a point in time. To measure something however, there must be a pre-existing thing what one will measure, this thing: time. What then is time, exclusive of the measurement of itself? What exactly is one measuring when one measures time? I am of a mind that what one is measuring when measuring time is the linear array of points-of-existence which the three-dimensional-world creates as is travels out into inexistence (inexistence being the nothingness which the Universe seems to expand out into). Time could be thought of as a fourth spatial dimension, in that it is a physical point of reference from the beginning of the Universe out to the point currently at which the Universe exists; just as width is a physical point of reference from the center of an object to its edges.

John Ellis McTaggart is an important name in temporal philosophy ever since the release of his paper The Unreality of Time in 1908. McTaggart proposed two series’ of time: the A-Series and the B-Series. The A-Series refers to temporal references such as ‘I tripped upon that snake five minutes ago’, whereas the B-Series refers to temporal references such as ‘I tripped upon that snake before having said this’. The A-Series inherently refers to tensed time: past, present, future; the B-Series refers only to the events occurring within time and how these events relate to each other (Stanford). McTaggart goes on to suggest that time could not be real due to change being “essential to time, and the B series without the A series does not involve genuine change (since B series positions are forever [‘]fixed,[‘] whereas A series positions are constantly changing)” (Stanford). For example ‘my wedding is tomorrow’ becomes ‘my wedding was yesterday’. If my wedding is tomorrow this is to say that my wedding occurs after the present moment, and to say my wedding was yesterday implies that my wedding occurred before the present moment. So how can my wedding take place before and after the present moment? Thus one has, McTaggart proposes, a paradox.

Bertrand Russelll seems to address the problem of the present in his own temporal philosophy, by eliminating it entirely. Russell proposes that the paradoxes inherent in temporal philosophy are due directly to the uncertain nature of the concept of present-ness, which is the moment of now, and to circumnavigate these paradoxes Russell coins his own temporal language to eliminate the present moment (Inwagen 77). This language looks something like this: ‘the moment at which I speak to you is the same moment at which I trip upon the snake’ or to be more directly non-present: ‘the moment at which I speak to you and the moment at which I trip upon the snake occur simultaneously’. Russell’s theory rejects the concepts of past, present, and future; it proposes then that there are only events which occur in a linear fashion and that any reference to time is simply a statement about the order in which events take place. So if there are only events which occur, and no stage upon which they occur, then what is it one has been measuring all these years with one’s clocks and calendars and dates and appointment books? Russell seems to think that one has been measuring the illusion of the differential of event-occurrences. This is preposterous however, as one may plainly see by way of a simple thought experiment. Imagine that there were no events, imagine that the physical world simply froze in place and all events ceased to occur. Would the ‘illusion’ of time then cease, alongside the cessation of the passage of events? No. Russell may rebut this experiment by claiming that the cessation of all events is itself an event and that one would therefore experience the illusion of its passage. I say no, and again appeal to a thought experiment: imagine there was never any events at all, imagine there is only a mind (your mind) and nothing else. Does ‘time’ still pass in this universe? It must for if time should not pass then neither would your thoughts, for your thoughts require moments in which to occur. Russell again may say that a mind being there is an event. Consider then the mind you inhabit is an observer outside of the universe of nothingness. Does time still pass?

Think now upon what I have to suggest regarding the nature of time, and see that it is by far the most reasonable theory of the three here mentioned, and perhaps of a larger grouping as well. One tends to consider time as some sort of essence which pervades all existence and ‘has things happen’ as it were.

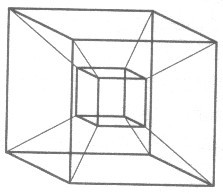

Figure 1.

When looking at a cube, see Figure 1, one experiences a three-dimensional object; the cube emits a perception of height, and one of width, and one of depth. Now, one contemplates said cube with said spatial properties existing in the same spot as it was created, and throughout the entirety of its existence does not so much as budge; yet one perceives a quaternary aspect of the cube due to the fact that the cube ‘continues to exist’, and this quaternary aspect is of a nature which is very difficult to define, although we have dubbed this perplexing phenomena Time. “What then is time? If no one asks me, I know what it is. Yet to explain it to him who asks, I do not know” (Augustine). McTaggart proposed that time is unreal, and I am inclined to concur with this thesis, however ‘time is unreal’ is not to say that time is not real, but more so to say that time is not as real as most things which one would consider to be real in an objective sense of reality, such as the cube, or one’s desk, or oneself. If one were to push the cube six inches to the left, one would have a relatively simple time explaining exactly why the cube is different after having been moved than before having been moved, but with the stationary cube, movement through time, this is much more difficult to explain. I propose that time is in fact a dimension of spatial-reconciliation.

“In our expanding universe, galaxies rush away from one another like a dispersing mob. Any two galaxies recede at a speed proportional to the distance between them: a pair 500 million light-years apart separates twice as fast as one 250 million light-years apart. Therefore, all the galaxies we see must have started from the same place at the same time -- the big bang. The conclusion holds even though cosmic expansion has gone through periods of acceleration and deceleration” (Veneziano).

Contemplate the precise moment the Big Bang banged, and imagine that the Big Bang banged-out a cube identical to Figure 1.

Figure 2.

See now Figure 2 and picture the inner-cube (hereafter referred to as Cube-One) therein as the universe at the moment-of-bang, and picture the outer-cube (hereafter referred to as Cube-Two) as the Universe at the next moment after the moment-of-bang. Now forecast your thoughts to envision the Universe after 14.7 billion years, worth of moments, of cubes extending outwards like this. The further along the array one is to observe, this is the spatial-dimension what is time. For Cube-One contains height, width, and depth (hereafter referred to as HWD), as does Cube-Two. Yet Cube-One’s HWD are different than Cube-Two’s HWD; how so? Firstly, Cube-Two’s HWD are more expansive. Secondly, and more crucially indeed, is the fact that Cube-Two’s HWD are each themselves moved from where each was in regards to Cube-One; how did they move though? For height itself can move neither higher nor lower, nor may width itself move left or right, nor may depth itself move in or out; and furthermore height may not move along width, or width along depth, or depth along height, for that notion is simply non-sensible. So just how did HWD move? One again asks. HWD moved along time, I answer. For if again one is to refer to Figure 1, and imagine that this cube is sitting on your desk and not moving, and after one hour the cube is still there on your desk. Is the cube in the same spot though? No! In fact after an hour the cube is 515, 000 miles away from where one left it to begin with, and for that matter so are you, and so is the desk! In relation to one another the objects remain in the same locations, but from a more expansive perspective one will note that all these things are speeding away from the center of the Universe; the Milky Way retreats at approximately 515, 000 MPH (818, 000 KPH) (Space).

Exclusive of the measurement of itself then, time is the distance outwards which any given point in the Universe has traveled since the moment-of-bang. In the equation T = dN - (oN + P), T is the degree of expansion of the Universe (referenced as Time), dN is the destination node of the Universe, being the point at which the Universe can no longer expand, oN is the origin node of the Universe, being the point at which the Big Bang banged, and P is the progress, at any given point, of the Universe on its outward trajectory from oN towards dN; also known as The Present. However, when one typically calculates time, one does not come up with a figure such as 14.7 billion years. One comes up with a figure such as 22:50, or 14:15. That is because humans have the need to speak relationally about time, and as a result have devised a system that chops any given moment out of the expansion of the Universe, and refers to it in relation to smaller and typically cosmic events, for example the rotation of the Earth on its own axis. Such a formula looks something like this P = oR + cR and T = P / 24 where P is progress calculated by origin of rotation (of Earth on its axis), plus current rotation, which is how far back towards oR the Earth has rotated. Then time is calculated by P divided by 24, which is a socially constructed number used to refer to ‘hours in a day’. A day is a reference to the Earth turning from oR around to oR, a full rotation. The reference is to how far outwards the Universe itself expands before Earth is able to rotate. Another commonly used reference is to the solar year. A solar year refers to the Earth travelling a full circle around the sun. While the Earth travels around the sun it is spinning on its axis and therefore cycling through days; the amount of time it takes for the Earth to travel around the sun is slightly in excess of three-hundred and sixty-five days, but for the sake of simplicity let us round down to a precise 365. So a solar year is calculated referentially: Y = D * 365 where Y is year(s) and D is day(s).

Mostly when one is hearing about, or is speaking about, time it is in the context of these referential manipulations of the true concept. Time is an extremely useful and versatile phenomena which is so engrained in the lives and mindsets of human beings that it is hardly ever analyzed beyond what one implicitly understands about it, being the socially constructed designations of but a shadow of True Time. Cosmologists and Astrophysicists are only recently beginning to bring True Time to light in the eyes and minds of the public as they begin to explore what might happen as the mathematics of the Universe continue to expand. As these scientists simulate time expansion it becomes increasingly questionable exactly what the Universe is fated to become. There is a chance the mathematics will hold together and continue to expand the Universe, but there is an equally likely chance that the mathematics will invert upon themselves (NASA). Should the latter be the case it will cause time to start travelling backwards and if time is only the expansion of the Universe, then inverted time is a contraction of the Universe, hence the name for this theory of time reversal ‘The Big Crunch’.

Works Cited

“Create The Cube”. 2014. Blackberry. Blackberry Native SDK For Playbook OS. Web. 24/09/2015, URL= https://developer.blackberry.com/playbook/native/documentation/tut_rotating_cube_opengl_projection_matrix_1935222_11.html

Markosian, Ned. "Time", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2014 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2014/entries/time/

NASA/WMAP Science Team. “Universe 101: Big Bang Theory”. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. 29/06/2015. Web. 02/10/2015. URL = http://map.gsfc.nasa.gov/universe/uni_fate.html

Red, Nola Taylor. “Milky Way Galaxy: Facts about our Galactic Home”. Space.com, 2013. Web. 29/09/2015. URL= http://www.space.com/19915-milky-way-galaxy.html

"Saint Augustine." BrainyQuote.com. Xplore Inc, 2015. 24 September 2015. URL= http://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/quotes/s/saintaugus108119.html

Smart, J.J.C. “Aristotle and the Sea Battle”. Problems of Time and Space. The MacMillan Company: New York, 1964. 43-57. Print.

Van, Inwagen P. "Temporality." Metaphysics. 4th ed. Boulder: Westview Press, 2015. 71-106. Print.

Veneziano, Gabriele. "The Myth Of The Beginning Of Time." Scientific American 311.(2014): 78- 89. Applied Science & Technology Source. Web. 21 Sept. 2015.

“Wireframe Display of Four-Dimensional Objects”. N.d. N.t. Web. 24/09/2015, URL= http://steve.hollasch.net/thesis/chapter4.html

No comments:

Post a Comment